More Italian Words and some More Shapes

(entry for 7/26/2024)

In the last post we talked about Italian and pseudo-Italian tempo and volume markings. Unfortunately, the matter which we covered, because of the limited space, was a bit abbreviated. This post will go into a bit more depth on those items, plus we’ll cover some musical ‘shapes’ that we haven’t discussed yet.

First, some additional aspects of tempo markings. In addition to the basic markings like Adagio and Presto, there are often ‘modifiers’ that are appended to those basic markings. There are also some other words that are used that change what has gone before without giving new absolute tempos.

One of the most interesting of these modifiers is the phrase ma non troppo, which means “but not too much.” For example, Allegro ma non troppo means “Fast, but not too much,” whereas Adagio ma non troppo means, “Slowly, but not too much.” The same modifier can also be added to other tempo indications, such as Vivace and Largo. (Note that the first word in a tempo phrase is capitalized, but the other words are not. They are all in bold however, and are not italicized, as dynamics are.)

I like to think of the phrase ma non troppo as meaning “but don’t overdo it.” (Some composers leave out the word ‘ma.’ They’ll say, for example Allegro non troppo when what they really meant was Allegro ma non troppo. Both phrases have the exact same musical meaning.)

Other modifying phrases include con fuoco and con brio, which mean, respectively, ‘with fire’ and ‘with spirit.’ Both are usually taken to mean tempos that are slightly faster than the un-modified word, such as Allegro. (It wouldn’t make much sense to mark something Largo con fuoco!)

Please note that these modifying words and phrases should not be used by themselves. They should follow one of the standard Tempo marks such as Lento or Andante.

By the way, any change from one capitalized tempo marking to another is instantaneous, not gradual. (We’ll get to gradual ones in a moment.)

Two more tempo indications that are quite common are Più mosso and Meno mosso. The first one means ‘More motion,’ in other words, faster. The second means ‘Less motion,’ in other words, slower. Again, these changes are instantaneous, not gradual. (And the first word is capitalized.) But you do have to know what the previous tempo was, because if you don’t, you’ll be asking yourself things like: “Slower than WHAT?” (Also, please notice the backwards accent mark on the word Più. If you don’t have that, you’ve mis-spelled the word!)

Now we come to the gradual changes. To speed up gradually is accelerando. To slow down gradually is either rallentando or ritenuto, take your pick. The corresponding abbreviations, which are often used instead of the full words, are accel., rallen., and rit. (Some people think rit. is short for ritardando. It isn’t. The short version of ritardando is ritard. Please also be aware that the abbreviations can be used with or without the period at the end. I prefer it with, as shown in these examples, but it's legal to leave it off.)

Two related words are allargando and ritardando. The first means to simultaneously get slower and louder. The second means to simultaneously get slower and softer. (I’m not aware of any single word that means faster and louder, nor one that means faster and softer. If you want to say ‘faster and louder,’ for example, you would say accelerando e crescendo. The lower case ‘e’ means ‘and.’)

To reiterate a bit, instantaneous changes in tempo are not italicized and the first word is capitalized. Gradual changes are also bolded, and not italicized, but they are not capitalized.

Also, be aware that the tempo mark goes above the staff, not below. (And in cases where there is a Grand Staff, such as piano or harp music, it goes above the top staff, not between the staves.)

There are many more Italian words related to tempo, but they are beyond the scope of this blog post.

Next we come to more words related to volume (loudness) besides the basic ones we covered last time. (All words of this sort are referred to as dynamics.)

The most common of these is sforzando. It means a sudden but temporary increase in volume, applying only to the note or notes it is written below. (Be aware that in vocal music, to avoid interfering with the lyrics, all dynamics are written above the staff, not below it. Also note that in Grand Staff music, most volume indications are between the staves, though there are rare excaptions.)

Here’s the sforzando mark as it would appear in an actual musical passage: (It's italicized like the whole word is, but it's in a special 'font' that is used only for musical dynamic abbreviations. Dynamic abbreviations, by the way, do not have a period at the end.)

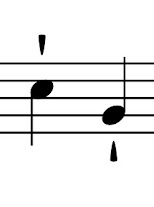

Which brings us to accent marks and other ‘expression marks.’ First of all, there are two different accent marks, and they mean two different things. The first one is fairly mild, and is called, simply, an ‘accent.’ Accents looks like this:

The next one is a bit heavier (both in looks and in meaning). It is called a marcato and it looks like this:

If you want something even heavier than a marcato, use the sforzando marking, above.

Note that the accent marks go either above or below the note-head, depending on the stem direction. (Or, in the case of stemless notes, on which direction the stem would go if there was a stem!) This does not apply to sforzando, by the way, which is placed the same as other dynamics.

Another common mark that goes above or below the note-head, as accents and marcatos do, is the staccato mark. It is simply a dot, but it must go directly above or below the note-head, not off to the side like a rhythm dot. (It is also slightly smaller than a rhythm dot, which goes to the side of the note-head, and which we will get to in a moment.) Here are some staccato dots:

The eighth notes here are staccato, whereas the half note is not. ( A staccato half note would be a bit contradictory, if you think about it!)

The exact meaning of a staccato mark is up for some debate. The Italian word means, simply, ‘detached.’ In music, it means that the note is separated from the other notes around it. (The opposite of staccato is legato, which means ‘connected.’)

However, different music theorists have different explanations for what ‘detached’ means in this context. Some would have us believe that a staccato passage like this one

should be played like this:

But most theorists leave the exact amount of detachment up to the individual performer, which is the approach I endorse. (I mean, we have to get to decide some things ourselves, right?!?)

Having mentioned the difference between staccato dots and rhythm dots, this would be a good place to talk about the latter.

A rhythm dot is placed to the right (and slightly above) the note-head it applies to. The meaning is very simple: 50% more. That is, the dotted note is 50% longer in duration that the undotted note. Another way of saying the same thing is to say that a dotted quarter note (for instance) means exactly the same thing as a quarter note tied to an eighth note. And a dotted eighth note is the same as an eighth note plus a sixteenth note. Etc.

In each case, the value on the left equals the value on the right: (They are just two different ways of saying exactly the same thing.)

You can add more dots, too. A half note with two dots after it means the same as an undotted half note, plus an undotted quarter note, plus an undotted eighth note. Etc.

Again, the value on the left exactly equals the value on the right. (The basic note, plus 50%, plus 50% of that.)

Dotted notes save a lot of space! (And you can legally have up to four of them on a single note-head, though that tends to get confusing to the performer. Two is probably the practical limit.)

Which brings us to two more new shapes: the tie and the slur.

Here’s a tie:

Here’s a slur:

A tie connects two notes of the same pitch. A slur connects two notes of different pitch. (If you look closely, you’ll notice other very subtle differences between a tie and a slur, but unless you’re a professional music notation engraver you probably won’t care!)

When a slur connects two notes, they are both played. (It usually means to play them legato, smoothly, although there are other meanings which we’ll cover in a later post.) When a tie connects two notes, only the first one is played; the second one is ‘held.’ Or to put it another way, two tied quarter note sounds exactly the same as a single half note. And an eighth note tied to a sixteenth sounds exactly the same as a dotted eighth.

One important point to be aware of is that three or more tied notes in a row must have ties that ‘touch’ each note-head, whereas slurs that cover three or more notes simply ‘touch’ (end at) the first note and the last.

In both cases (except in vocal music) they go below the staff, along with all other dynamics.

*

copyright © 2024, LegendKeeper LLC

*

If you’d like to see other entries in this Music Blog series, please click HERE.

They will be listed in reverse order of publication, with the most recent first. (If you want to read them in order, go to the bottom of the list!)

If you’d like to see entries in my Memory Blog series, please click HERE.

(Reverse order of publication.)

Comments

Post a Comment