The Wedge for Minor Keys

(entry for 1/31/2025)

Most printed Circle of 5th Charts that you can buy, and most of the printable ones you can find online, have one fatal flaw in common: They assume that the Roman numerals for Minor Keys are the same as for Major Keys.

This simply cannot possibly be true. Think about it: if the Roman Numeral is the number of the note value in the scale in that key, then the ‘home note’ for the key you’re in must be a ‘one.’ To be sure, it’s a lower case ‘i’ rather than a capital ‘I,’ because the chord is minor, but it still has to be a ‘one,’ not a ‘six,’ because it’s the home note of the scale.

For example, let’s say we’re in the key of d-minor. The circle layout is the same, but the wedge isn’t. If the wedge for the key of one-flat is at eleven o’clock on the wheel, and if the key is d-minor rather than F major, then the ‘home chord’ for the d-minor key is where the ‘vi’ would be if we were in major. But it has to be the numeral ‘one,’ if that’s the actual key we’re in.

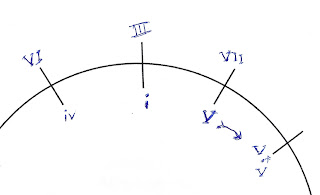

So the whole wedge has to get re-numbered, and the result is at the top of this post. (We’ve included the V of V in the picture, too, as that will be important later on in the post.)

You’ll notice two things about this new wedge right away:

1. There is now a numeral ‘seven,’ where before there was not. And there is now no numeral ‘two.’

2. There are now four major chords (capital letters) and only two minor chords (lower case), where before there were three of each.

Let’s deal with the second point first. The secret here has to do with our friend, the ear. We had mentioned in an earlier post that the idea of ‘minor’ grew out of the Aeolian Mode, and that we ended up with three different varieties of minor: the natural minor, the harmonic minor, and the melodic minor. And you may also recall that the natural minor is exactly the same thing as the Aeolian Mode itself, where it came from.

But when we’re talking abou the Circle and the Wedge, we’re talking about harmony, so only one of the three kinds of minor is involved: namely, the harmonic minor. But the harmonic minor scale has that raised seventh degree. (G-sharp in the key of a-minor.) But if you put a G-sharp into an E chord (the numeral-‘five’ chord in a-minor) it becomes an E major chord, not an e-minor chord. So we have to show the V as a capital V, even though it’s on the inner part of the circle. Important: the V chord is always major, whether we’re in a major key or a minor key. This is the only chord that the statement is true of. All other chords in the wedge switch ‘case’ when we go from major to minor or vice versa.

Why? Because our ear demands it. To us, if we make the five-chord minor, it sounds ‘modal’ rather than minor. That’s because it is! If the five-chord is minor, then we’re in Aeolian Mode, not in harmonic minor. In order for the chord to sound minor rather than modal, we have to use the harmonic minor, and, as we’ve seen, that gives us the V major chord in any minor key.

So, when we’re in minor keys, the circle doesn’t work perfectly. Let’s say we’re in the key of b-minor (two sharps). The circle says that in this wedge (if we are in D major rather than b-minor) the outside of the circle chords, from left to right, are G major (the IV chord), D major (the I chord), and A major (the V chord). Likewise, the inside-the-circle chords (the minors) are, again left to right, the e-minor chord (the ii chord), the b-minor chord (the vi chord), and the f-sharp minor chord (the iii chord).

BUT! If we’re in b-minor, not D major, that f-sharp minor chord has to become major, in order to remain harmonic! So instead of a nice even circle, the revised one has to look like a gear wheel, with ‘sprockets.’ Here’w what that looks like at the top of the circle.

Some online Circles do show this sprocket effect (though most do it in much ‘prettier’ fashion than I have done it here), and a few that you can buy do also, but they also incorrectly leave the numbering the same for either major or minor, and this has to be wrong, as we have seen.

So, instead of making a ‘gear-wheel’ out of the circle, I prefer to leave it nice and circular, and just show the change in a new Wedge, made for minor keys. The capital letter V in the lower right corner serves as a reminder that the V chord is always major, and it ‘over-rides’ the minor chord showing through from underneath.

Now let’s go back to the first point of the two above. Why has the numeral-two chord disappeared and been replaced (although in a different spot) by the numeral-seven chord?

It’s very simple. The two chord is now diminished, not major or minor. And the seven chord is now major, not diminished any more. And since we allow only major and minor chords in our wedge, we had to banish the ii chord and welcome in the VII one.

(The answer also has to do with the seventh partial, if you go back to that post. As mentioned there, the seventh partial does not fit our ‘Western’ harmonic scheme, and the second note of the minor scale IS that seventh partial. That’s the real, underlying reason we had to banish the ii chord from our new wedge.)

Songs written in minor keys are tricky, because of this change in the Wedge. There are a lot more major chords in a minor key than there are minor chords in a major key. This all goes back to the very early post about the Series of Partials, where we learn that the major triad is part of every note we ever hear, and the minor triad is not. That’s the real reason our ear likes major better— we’re more used to it, because we hear it in every note we hear.

Which brings us (finally) to why we included the V of V chord in the illustration at the top of the post.

Just as V of V sometimes plays a role in major keys, it also plays a very important role in minor keys. In fact it’s more common in minor than it is in major.

When we need to go ‘outside the wedge’ in a minor key, the most common way to do that is to ‘step out’ clockwise, and when we do that, the former V chord becomes the new ‘One’ chord, temporarily, and the V of that is then the V of the original V. Do if you’re in the key of d minor, your V chord is A major, and the V of that is E major. But if you try to show this with the circle, rather than with the wedge, it becomes very confusing. (As if it wasn’t confusing enough already!)

The next post in this series will be the last one, and we’ll summarize all the things we’ve discovered (or remembered) throughout the series.

*

copyright ©2024, LegendKeeper LLC

*

To see an index of all of Len’s Music Blog posts, please click HERE.

To see an index of his Memory Blog posts, you can click HERE.

Comments

Post a Comment